Follow the gleam

Posted on September 16, 2013 Leave a Comment

I’d never been to Rome before.

Just as I’d never been to Vienna. Or Prague. Or Berlin. Or Copenhagen. Or any number of other places I just got through visiting on my two-month-long, very-low-budget, round-about tour of Europe.

Then again, there was an earlier time in my life when I could have said the very same thing about Alaska, or Washington, or Oregon.  Or before that the northern half of my home state of California. And before that certain parts of my home town of Long Beach. And before that anything beyond the nine-block walk to my kindergarten class, which use to mark the very edge of my 5-year-old world.

Or before that the northern half of my home state of California. And before that certain parts of my home town of Long Beach. And before that anything beyond the nine-block walk to my kindergarten class, which use to mark the very edge of my 5-year-old world.

So that’s the point.

Each journey pushes out the margin of our known world farther and farther, in one way or another, as long as we live. Just as that aging mariner-king Ulysses described it in the Tennyson poem (which I cited at the very beginning of this journal):

I am a part of all that I have met;/ Yet all experience is an arch wherethrough/ Gleams that untravelled world, whose margin fades/ Forever and forever when I move … / And this grey spirit yearning in desire/ To follow knowledge like a sinking star/ Beyond the utmost bound of human thought.

Personally I don’t think of myself as a grey spirit, but I understand how Ulysses might have felt about following knowledge “like a sinking star,” because the pursuit of new people and places was easily the most pleasant part of my trip.

I mean, let’s face it: Rome is pretty special.

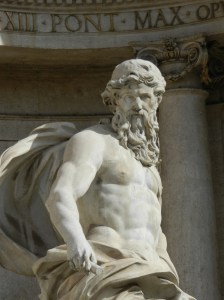

Since I had four days there prior to catching my flight home, I’d ample opportunity to “see the sights” — the top tourist attractions — from the Colosseum, to the old Roman Forum, to the Trevi Fountain, to the Spanish Steps, to the Vatican with its St. Peters Basilica and Sistine Chapel. And (happily) I was seeing them in September — after the crush of August tourists had already come and gone and summer’s heat had lost its grip. There was even a rumored pope-sighting.

Since I had four days there prior to catching my flight home, I’d ample opportunity to “see the sights” — the top tourist attractions — from the Colosseum, to the old Roman Forum, to the Trevi Fountain, to the Spanish Steps, to the Vatican with its St. Peters Basilica and Sistine Chapel. And (happily) I was seeing them in September — after the crush of August tourists had already come and gone and summer’s heat had lost its grip. There was even a rumored pope-sighting.

But I also had a chance to simply take a nice long walk from one side of Rome to the other, passing through a variety of neighborhoods. And you can’t do that without marveling at how virtually every three blocks contains some new ancient relic of our past that Romans just take for granted.

And you soon see why some of the very first tourists — Barbarian invaders from the north — would have found Rome so appealing, just as we might today. Because, as a species, we’re always looking for the next “best place” to live. And just in case we need reminding, all of us are immigrants.

I once mailed $100 to the National Geographic Society so they could send me a DNA cheek-swab kit that would tell me where my “deep ancestors” came from. When I received it, I followed the simple instructions — brushing the inside of my mouth with the swab, then placing it in a vial — and mailed my sample back to technicians at the society’s Genographic Project.

Did I say “deep ancestors”? I meant really deep, like from the origin of Homo sapiens in Africa with the “genetic Adam” and “genetic Eve” of 200,000 years ago, through millennia of good times and bad times, until, about 50,000 years ago, the ancestors of everyone alive today began to experience a climate that produced lush grasslands and plentiful game in the Middle East that lured “out of Africa” a huge wave of our ancestors. Including mine.

The DNA lab results said that the thin, strictly-patrilineal branch of my family tree (which can be traced through a male’s y-chromosome) ended up in western Europe about 30,000 years ago. Which might explain why my great-great-great grandfather was living near County Donegal when the great Irish potato famiine of the 1840s encouraged him and his siblings to seek a “better place” in Boston.

But the moving on wouldn’t end there. My great-grandfather would seek an even better place in the mining towns of eastern Colorado. And my grandfather, with my dad in tow, would likewise move on to California. Just as my brother and his wife (and later myself) would choose to move from there to Alaska.

Yes, we’re always looking for the next best place — or at least a decent job. For a good long while in America, that immigrant wave was always rolling west. But ever since it crested in Alaska, I can’t help but wonder if it might not finally break back on itself, tossing my three daughters back east. Maybe. And maybe not. We all have to follow the gleam.

Under the Volcano

Posted on September 13, 2013 2 Comments

I was getting very close now to Rome. Still I couldn’t resist one more turning in the road — this time to Pompeii — to stand in the ruins of a once thriving town and look up at Mount Vesuvius.

As schoolchildren many of us were told about its epic eruption in the year 79 AD that buried Pompeii, killing thousands of residents. What I didn’t realize, however, is that Vesuvius remains the single most active volcano in Europe.

In preparation for a hike to its summit, I learned Vesuvio (in Italian) erupted six times in the 18th century, eight times in the 19th century, and the first time it erupted in the 20th century — on April 7, 1906 — the volcano killed more than 100 people and damaged a good portion of nearby Naples. Rome then was on the brink of hosting the 4th Olympiad, but so much money had to be diverted to rebuilding southern Italy that the 1908 Games were moved to London instead.

In fact a strong case could be made that Vesuvius today is the most dangerous volcano in the world — since more than 4 million people now live in the greater metropolitan area of Naples, which virtually lies in its shadow, six miles to the west. Little Pompei is just as close to Vesuvius to the south, and that’s the direction the wind was blowing when it erupted in 79.

Standing there this week in ruins that were once buried more than 10 feet deep in ash, I tried to imagine what that day must have been like for all the parents and children in town. To a remarkable degree, we already know — thanks to the eyewitness account of a Roman poet and letter-writer known as Pliny the Younger, the preservative effect of the ash itself, and, of course, all the sleuthing and digging by modern-day archaeologists and volcanologists.

They now estimate the eruption shot millions of tons of rock and ash 20 miles high with 100,000 times the thermal energy of the bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima. Soon the ash cloud cooled and began to rain down on Pompei like the world’s worst hailstorm.

Most of the town’s 10,000 residents took that opportunity to escape, finding refuge in villages to the north, away from the ash cloud, or in the open sea to the west. For more than 2,000 residents who remained behind, however, the worst was yet to come.

It arrived during the night in the form of a ground-devouring wave of gas, fire and molten rock — what geologists call a pyroclastic flow — racing downslope at perhaps 100 mph, incinerating everything in its path. Additional pyroclastic surges followed the next day.

One of its victims was the uncle of Pliny the Younger — Pliny the Elder — who observed the eruption from 15 miles away the day before and sailed to Pompeii to assist on the beach. He died trying to help. (If you’re interested, there’s a nicely written story that appeared in Smithsonian Magazine a few years ago with amazing specificity on what various victims of Vesuvius were doing at the moment they perished.)

It’s reasonable to wonder: Why would so many people, both then and now, choose to live so close to a volcano? And there’s a pretty good answer — one I was able to observe firsthand as a bus transported me to the Vesuvius trailhead high on its upper slopes. Namely, that the ash it emits to the surrounding slopes and lowlands results in a very dark, rich and fertile soil that’s excellent for growing crops. And if devastating eruptions only occur once a millennium or so — who’s to remember?

Here’s what I’ll remember: Hiking briskly up the final mile of trail to the summit of Mount Vesuvius and then looking over the rim into the (temporarily) rock-solid caldera — and thinking about its hidden power and terrible beauty and all those 1st-century families below.

The bus tour I’d joined had advertised the experience as a chance to “walk around the circumference of the rim,” and that’s what I intended to do. But the driver also told me I needed to return to the trailhead in a half hour if I expected to catch my train for Rome (and home). So I needed to finish my own circumnavigation at a jog, then pick up the pace going down. Which out of necessity is exactly what I did. And that’s what I’ll remember: Jogging in the sun around the rim of Vesuvius, then running to catch a train going down.

Back to Italia

Posted on September 10, 2013 Leave a Comment

Sometimes you wander. Like Dante, you go astray. Like Ulysses you take a wrong turn or two. Then one day you wake up and a month has gone by and the rest of your crew is all back home and you’re by yourself somewhere north of Oslo and wondering how you got there.

When something like that happens, it’s no use making excuses. None of them would sound very convincing anyway (least of all to an editor who’s been trying her best to reach you). The best you can do is get back to Rome (to catch a British Airways flight back home). So this is just to say: I’m getting close — as these images of Cinque Terre and Siena and Florence can attest.

From here I think I know The Way. But the fishing was good in Riomaggiore. And though I missed the horse race season around the square in Siena, there was this festival of the Wolf contrade that slowed things down. And Florence — well who would have guessed that in the cupola of the Duomo alone there are 463 steps and more than a few frightening pictures …

Past-imperfect Prague

Posted on September 8, 2013 Leave a Comment

“God gives us nuts, but doesn’t crack them.”

— Czechoslovakian author Franz Kafka

My guide on a free walking tour of Prague this summer repeated that line to us after pointing out Kafka’s statue in the old Jewish Quarter, then gave everyone a moment to reflect on how that must mean God gives you opportunities, but it’s up to you to succeed.

Perhaps, I thought. Or it could mean that life in Prague is tantalizing … but ultimately wanting. Or it could mean that God just breaks the nuts over your head.

Why would I think that?

Because I’d been taking careful notes during the tour, and what I’d recorded about Czech history so far was nothing less than a thousand years of invasions and occupations and religious cruelty and terrible town-killing plagues. Like when do you get the nuts?

On the other hand, I loved visiting Prague. I liked the people and the place. The old streets, the medieval architecture, the bohemian vibe, the way it lights up at night. I liked the affordable prices and excellent beer.

I loved the fact that a playwright and political dissident — the once imprisoned Vaclav Havel — could ultimately prevail over the former Soviet Union and be elected the first president of the new Czech Republic in a “Velvet Revolution.” I liked the way Havel befriended the Rolling Stones, who paid for floodlights to shine on Prague Castle.

Others must like Prague too. It’s home today to about 1.3 million people, and summer tourists flock there in droves. (According to the Czech Republic tourist council, Prague hosts about 4 million visitors annually, making it the sixth most visited city in Europe.)

On the other hand, there was all that gruesome history.

Where to begin? With the early humans who pushed out the Neanderthals? With the Germanic tribes who pushed out the Celts? With the Slavic tribes who pushed out the Germans? Or about a thousand years ago when a pope in distant Rome declared the whole kingdom of Bohemia (roughly the present-day Czech Republic) as a diocese of the Holy Roman Empire.

Consequently several significant Catholic cathedrals rose in old Prague, which really began to cohere as a town in the 10th century. Its hey-day probably came in the 14th century under King Charles IV, when Prague was the third largest capital in all Europe, trailing only Rome and Constantinople. But it was a qualified hey-day. In the middle of the century the Great Black Plague in Europe killed 25 million people.

Then things got worse after they got better. In the 15th and 16th centuries, scandals in Rome had inspired the reformist message of northern Catholic clerics like Jan Hus and Martin Luther, which led to the founding of the Protestant (for “Protester”) religions. So Northern Europe went Protestant, Southern Europe remained Catholic, and Central Europe was where the two would collide — again and again — in Prague.

It wasn’t long before Christian-on-Christian violence there resulted in public beheadings and defenestrations. (Being “defenestrated” is when they avoid the bother of putting you on trial and simply march you up the tallest tower and throw you out the window.)

Life was even worse if you were Jewish and all the Christians despised you. In Prague that meant that for centuries you were forced to live in a plague-infested swampland next to the Vltava River and nowhere else. And as the population there grew, there was less available land in the Jewish quarter in which to live — let alone be buried in. Because when you died, you could only be buried in the tiny Jewish cemetery and after a while there wasn’t any room left.

So the Jews of Prague would carefully detach all the tombstones from the ground (leaving the bodies in place), bring in a new layer of soil, stick the old tombstones back on top where they were and start a new layer of burials, with the combined tombstones crowding ever closer and closer together. And so it went for centuries. According to three sources cited in Wikipedia, there were eventually 12 layers of Jewish dead buried in the Prague cemetery, possibly 100,000 to 200,000 bodies in all. As Petra, our tour guide, pointed out, the ground there is now higher than the perimeter retaining wall.

Reforms in the Holy Roman Empire that eventually came in the 18th century gave Jews in Europe more freedom, and for a while their lives improved. But the cemetery would live on in infamy — as an anti-Semitic legend suddenly emerged around the turn of the 20th century claiming that Zionist Jews were meeting there secretly at night to hatch a plan to rule the world. This imagined Zionist conspiracy in the Prague cemetery was one of the reasons to purge Jews from all of Europe that would later be cited by Adolph Hitler.

But that’s getting ahead of our history. Here’s the rest in a nutshell. Beginning in the 16th century and lasting for the next 400 years the people in Prague were ruled by people in Austria who spoke a different language (the House of Habsburg dynasty, which for a while was synonymous with the Holy Roman Empire). Along the way religious infighting continued (see “Thirty Years War”).

World War I came and went and that ended the Habsburg rule in Prague and created the new nation of Czechoslovakia, which combined the people of Bohemia and Moravia. That happy state lasted for about 20 years — until Hitler invaded Czechoslavakia in 1939 and World War II began. During the war, a majority of the Jews in Prague were deported and executed by the Nazis. After the war, the Soviets moved in and, well, you probably know the rest of the story: Twenty years of worsening conditions under the Communists. The “Prague Spring” of 1968 (and the Soviet crack-down that crushed it). The Gorbachev/Glasnost era in 1988 (and the collapse of the Soviet Union that followed). The Velvet Divorce of 1993 (dividing Czechoslovakia in two and creating the new Czech Republic).

All of which brought the story full-circle back to my tour guide, Petra. She was born in Prague in 1980 and lived nine years under the foreign auspices of the Communists.

“Everything was grey then,” she told me. “There was no food. There was no freedom of speech or religion. There was no travel abroad. You were forced to spy on your neighbors.”

Life in Prague now is immeasurably better, Petra said. But after a thousand years of foreign occupation, her neighbors — indeed all Czechs — remain understandably a bit cautious and wary. They’re staring into the light of a brand-new day where — who knows? — maybe they’ll find some nuts.

Garden of brains and bones

Posted on September 7, 2013 Leave a Comment

Let’s give the French their due.

Before English naturalists and American geneticists began receiving so much credit for break-through discoveries in the Life Sciences — from Darwin to DNA — you first had to collect, compare and categorize as many species as possible.

And for that you had to travel to Paris.

More specifically, you had to visit the remarkable collections of late 18th and early 19th century French zoologist Georges Couvier, an expert on everything from beetle skeletons to fish fossils to wombat brains.

And you can see them still if you find your way — as I just did — to the Jardin des Plantes (the spacious botanical garden in central Paris) wherein you’ll find the various galleries of the world renown Museum d’ Histoire Naturelle.

Today the French natural history museum (actually several museums) houses a breath-taking total of 65 million specimens, including the largest paleontological collection in the world, thanks largely to Couvier, who’s widely considered the father of paleontology.

But just by chance I happened first into the stately Paleontology and Comparative Anatomy Gallery, where you can stare into the jaw of an ancient 30-foot-long crocodile (see slide show below) or compare the brain size of hundreds of tiny mammals.

I’ve visited spectacular natural history exhibits before at the Smithsonian and the British Museum of Natural History, but something about the Galerie was more fascinating, like peeking into the private chambers of the world’s greatest naturalists back when Darwin was only a boy.

According to the museum catalogue, however, its collection is anything but musty or dead to science — given the capability today of extracting DNA from ancient specimens to trace their genetic and evolutionary pedigrees. After sleeping for a century or so, it’s now a treasure trove of new scientific research.

I also had a chance to visit — across the botanical garden — the newer and much more avant-garde Grande Galerie de L’Evolution, with it’s Noah’s Arc procession of large mammals and interactive media. Though it’s amusing (if not agravating) to find no English translations at all. O the French!

I was also getting hungry. So before catching my evening train to Nice, I took a stroll along the Seine to find a place to eat. After slowing down as I passed all the book stalls and street musicians, I decided just to picnic on the bank and watch the setting sun. That and the great parade of humanity that passed by. The most fascinating exhibit of all.

Going Dutch

Posted on September 7, 2013 2 Comments

What if people on bicycles ruled the road? Not truck drivers. Not motorhome highway hoggers. Not even the galactically mindless males driving their dad’s pick-up trucks around Anchorage. But people like you and me — on bicycles.

Well, I’m thinking that world might look a lot like Amsterdam.

Bicycles in the Dutch capital easily out-number cars. They even outnumber people. According to the latest city-sponsored study, there are about 1,000,000 bicycles shared by Amsterdam’s 820,000 residents and, on average, each household owns about four.

All that digital information became real for me last weekend as I stepped outside an Amsterdam train station and saw assembled there the largest collection of bicycles I’ve ever seen parked in one spot.

These weren’t abandoned bikes, though a majority of them looked pretty beat-up (as if they were all competing for the honor of being “least desirable bike to steal in The Netherlands”). No, these were bicycles that were very much owned and loved and waiting for someone to finish work and ride them back home.

And when Amsterdam bike riders want to go somewhere, they aren’t marginalized off the real roads onto some cute, winding, asphalt strip in the trees. They have their own serious super-highways (or so it seems) and cars and pedestrians better steer clear. Sometimes that’s hard to do — when the sidewalk for pedestrians narrows down to next-to-nothing and the adjacent bike lane is undiminished.

Walking around Amsterdam for a couple of days, there were at least a dozen times I accidentally stepped into a bike lane and nearly got vivisected. But here’s the thing: No one ever hit me, or yelled at me, or even looked frustrated. Instead the rider would merely make some slight adjustment to his or her course and whiz on past, having already anticipated the encroachment.

These guys are good. And they aren’t dressed in bike-riding gear like American cyclists usually are. They wear their professional work clothes, oftentimes suits or casual clothes for the men and breezy summer dresses for the women. Hardly any of them wear helmets. I counted only about one in twenty with head protection. And that was true as well for the children being chauffeured around by their parents.

I desperately wish I had my camera ready when a mother with a newborn baby tied to her bosom in a Snugli soared past. Or when a father rode by with a kindergarten-aged boy standing absolutely upright on the back-rack (holding onto his dad’s shoulders) and behind the boy also standing upright a small girl holding on to her brother’s shoulders.

But on the last Saturday in August — with polished blue skies and tree-lined canals interspersed every few blocks — Amsterdam was pretty nice for walkers too. Especially in the huge park-like Museumplein, where sidewalk food, playgrounds, Heineken stands, cultural booths, free entertainment and some of the world’s finest museums all blended together into one big Dutch picnic.

I’ll let you guess, from the slide show images below, exactly which museum I decided to visit there that features the work of exactly which native son. As a bonus, I’ll save you all the awful ear jokes.

Olympic Dreams

Posted on September 4, 2013 Leave a Comment

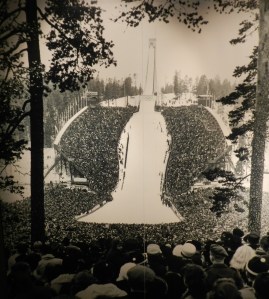

If Anchorage truly wants to host the Winter Olympics — as its current mayor and a former mayor are hoping it will — the city would be well advised to send emissaries to Lillehammer, site of the 1994 Winter Games. But I doubt that they ever will.

Why Lillehammer?

Longtime Alaskans might recall that about a quarter century ago this handsome little community in central Norway beat out Anchorage in the international competition to host the next Olympics. Good thing it did. When the winter of 1994 rolled around, Anchorage was virtually snowless. Lillehammer, meanwhile, was not only looking like a winter wonderland, but the town itself — and all of Norway, for that matter — was drawing rave reviews around the world for having hosted the best Winter Games ever.

What much of the media, including magazines as influential as Sports Illustrated, appreciated wasn’t only Norway’s spectator-friendly management of the Olympics — which was pretty near flawless — but the overall generosity and humanitarian spirit of the place. Its healthy lifestyle. Its obvious love of winter.

In Lillehammer in particular, you saw all these little innovations for life in a northern city that Anchorage might do well to emulate. Like the pedestrian-minded city planning. The colorful and durable housing. Even the little foot-powered ski-scooters the residents pedaled around on whenever the snow got ahead of the snowplows.

Nineteen ninety-four was also the year that newspapers as modest and mid-sized as the Anchorage Daily News, my former employer, still had the resources (and the resolve) to send a staff writer half-way around the world to report first-hand on the Olympics. If memory serves, the designated reporter back then was now long-time ADN sports editor Beth Bragg, and her chief subject-of-interest was Alaskan alpine skier Tommy Moe. I think it turned out well for both of them.

To nearly everyone’s surprise, Moe ended up flying down the mountainside without fear or favor again and again, winning a gold medal in the downhill and a silver in the Super G — the first time ever an American male skier had won two medals in a single Winter Olympics.

All of this happens to be on my mind right now, because I just got through touring Oslo. And while I was there, I decided to catch a train north to Lillehammer and compare my memory with the here and now. Of course it’s still summertime here and the ski slopes in Norway are as green as August in Alyeska. So was the synthetic surface of the massive Lillehammer ski jump, lying idle in the sun.

Right next to it, however, the Olympic hockey arena was busily preparing for a sports exposition associated with Norway’s largest long-distance mountain-bike race. I walked around it to find the entrance to Lillehammer’s inspiring Olympic Games Museum.

Norway has plenty to be proud of in that regard. Even with its relatively tiny population of 5 million citizens, it still leads the world with the most Winter Game medals overall (with 303) — to second-place United States’ 253.

Inside the museum — which also records the history of the Summer Games — you walk down a cavalcade filled with huge photographs of Olympic stars through the ages, from American track athlete Jesse Owens on the summer side to Norwegian speed skater Johann Koss in the winter.

You see images of Super-Bowl-sized crowds in 1940 circling the old Oslo ski jump. And crowds just as huge in Lillehammer clamoring to watch cross-country ski races. (According to a 1994 report in the New York Times, Lillehammer organizers were amazed to receive a quarter million requests for just 30,000 tickets allocated to cross-country ski and biathlon races. So they did the only sensible thing they could do: they surrendered, announcing that anyone with the energy and desire to snowshoe or ski into the woods was darn well welcome to watch those events for free.)

But the Games weren’t free. According to that same NYT report, the Norwegian government and private donors spent $1 billion (in 1994 dollars) just preparing Lillehammer for the Games — from boring traffic tunnels underneath the city to building an entire Olympic Village, which they converted to housing for the elderly once the Games were over.

Which kind of brings the whole spendy subject back to Anchorage. What makes its chances any better this time around? Who’ll be picking up the tab? And are we really willing to bet the village that a chinook won’t come around and eat up all the snow?

Us dreamers want to know.

My Nobel Surprise

Posted on September 3, 2013 1 Comment

You know you must have finally become an Alaskan when the summer that you’ve enjoyed abroad eventually grows a little too balmy and predictable and you find yourself longing for a good old autumn williwaw.

That’s what made my brief journey from Central Europe to Stockholm so pleasant last week, smelling northern seas again, hearing the cry of seagulls and the sharp blast of a ship’s whistle. Like that first trip north to a long-ago Seattle, boarding the Malaspina bound for Haines.

Walking up a narrow, lamplit street in the early evening, I found my hostel and room beneath the old clock tower, stowed my pack — then stepped back out again to explore the harbor and find a place to eat.

Thinking about it now, I can see how it sounds a little counter-intuitive to travel from Italy to Scandinavia, only to order the Napoli pizza, but that evening I was in the mood for seafood, and the Napoli with anchovies was by far the most affordable option.

(I’ve tried hard not to be the American who comes as a guest to a foreign land and ends up whining about the prices, so I’ll try not to do that here — except to briefly say that in the current state of hyperinflation in Copenhagen, Stockholm and Oslo, a sit-down dinner usually starts at about $27 U.S., and that’s just the fish and chips.)

My pizza, however, was huge and delicious — just the right balance of vegetable and protein — and the Heineken made it perfect. So I decided to end the evening with a little window-shopping on my way back to the hostel.

I passed shop after shop filled with colorful toys and stylish clothes and that knack for classy design for which the Swedes are deservedly famous. Happily, though, I also found some class-free shops, including one with a sign that begins to express my personal bias for dogs over cats (see slide show below).  And another with a t-shirt celebrating the first “Viking World Tour: 793 (A.D.) England, 795 Wales…” — glossing over what happened along the way.

And another with a t-shirt celebrating the first “Viking World Tour: 793 (A.D.) England, 795 Wales…” — glossing over what happened along the way.

I also passed the famous Swedish Academy with its adjoining Nobel Prize Museum. It was closed that evening, so I thought about visiting it the next day. And now I’m glad I did.

For one thing, did you know that some Nobel Prize winners actually have a sly sense of humor? Well, I didn’t. But here’s the evidence, gleaned from a book of quotes from Nobel Laureates I bought in the museum gift shop:

“History will be kind to me, for I intend to write it.”

— Winston Churchill, Nobel Prize for Literature, 1953

“In any case, let’s eat breakfast.”

— Isaac Bashevis Singer, Nobel Prize for Literature, 1978

(To his wife, on hearing he had won the Nobel Prize.)

“Christianity might be a good thing — if anyone ever tried it.”

— George Bernard Shaw, Nobel Prize for Literature, 1925

“Unless a reviewer has the courage to give you unqualified praise, I say ignore the bastard.”

— John Steinbeck, Nobel Prize for Literature, 1962

“The disputes are so bitter because the stakes are so small.”

— Henry Kissinger, Nobel Prize for Peace, 1973

(On university politics)

“At the Novosibersk Transit Prison in 1945 they greeted the prisoners with a roll call based on cases. ‘So and so! Article 51 and 58-1A, twenty five years.’ The chief of the convoy guard was curious. ‘What did you get it for?’ ‘For nothing at all.’ ‘You are lying. The sentence for nothing at all is ten years.'”

— Alexandr Solzhenitsyn, Nobel Prize for Literature, 1970

“If my theory of relativity is proven correct, Germany will claim me as a German and France will declare that I am a citizen of the world. Should my theory prove untrue, France will say that I am a German and Germany will declare that I am a Jew.”

— Albert Einstein, Nobel Prize for Physics, 1921

The museum proper just then was focusing on the 100-year-plus history of the Nobel Peace Prize — especially the growing need for it these days — and there was much there to both admire and regret.

Of course there is no small irony in the fact that Alfred Nobel himself — the Swede who made a fortune inventing, manufacturing and selling explosives — would posthumously dedicate that fortune to promoting peace with the world’s most prestigious prize, as well as honoring with medals (and million-dollar-cash awards) great strides forward in the sciences and humanities.

But I think the world should be glad he did. Just as I was glad to explore his museum that afternoon (my own Nobel prize) and read once again those inspiring words spoken by the American writer William Faulkner upon accepting the honor for literature in 1949:

“I decline to accept the end of man… I believe that man will not merely endure: he will prevail. He is immortal, not because he alone among creatures has an inexhaustible voice, but because he has a soul, a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance. The poet’s, the writer’s, duty is to write about these things. It is his privilege to help man endure by lifting his heart, by reminding him of the courage and honor and hope and pride and compassion and pity and sacrifice which have been the glory of his past.”

Road to Sachsenhausen

Posted on August 27, 2013 6 Comments

“It seemed as impossible to conceive of Auschwitz with God as to conceive of Auschwitz without God.”

— Elie Wiesel, 1986 Nobel Peace Prize lecture

On my way from central Europe to Scandinavia last week, I stopped off in Berlin to visit for the very first time the former beating heart of Hitler’s Germany. How could anyone of my generation not? If you happened to be born in America in the middle of the 20th Century (say between 1940 and 1960) the history you absorbed as a child — in school, on TV, at drive-in theaters — was replete with images and stories of Nazi Germany, and that continued well into adulthood. From Victory at Sea to Judgement at Nuremberg. From Sound of Music to Sophie’s Choice. From The Great Escape to Schindler’s List, Germany was on our minds.

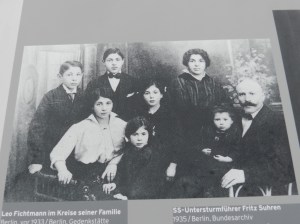

For me Berlin was the attraction. But I’d heard too that on the edge of town, in the sleepy bedroom community of Oranienburg, there still stood the remnants of a former Nazi concentration camp, one most Americans have never heard of. Its name was Sachsenhausen. And from the day it was covertly built by Nazi SS (Gestapo) chief Heinrich Himmler in the summer of 1936 — the very same summer Berlin was otherwise happily hosting the Olympic Games — it fulfilled a very special purpose, serving as the camp next door to the national SS headquarters and as a model and laboratory for all the Nazi death camps to come, from Dachau to Auschwitz.

I intended to visit Sachsenhausen, but not immediately. First I wanted to see Berlin on a larger canvas with all its history — from its origin as a fish camp for Slavic-speaking pagans in the Middle Ages to its surprisingly late (18th century) start as a town to its central role as capital city of all of Germany’s recent iterations (Kingdom of Prussia, 1701-1871; German Empire, 1871-1918; Weimar Republic, 1918-1933; Third Reich, 1933-1945) — to everything after that, including the here and now.

And I did.

I saw blues clubs that seem to value the African-American experience even more than a lot of Americans do. I saw handsome parks while strolling Unter den Linden and picnicking in the Tiergarten. I saw one of Berlin’s world-famous museums, including a current exhibit of Queen Nefertiti and early-Egyptian artifacts. I saw the glass dome of the remodeled Reichstag — the national capitol — meant to convey both the transparency of a true democracy and also a new relationship in which government leaders (seated at the bottom of the dome) are subservient to the public (touring and observing from above). Nice, I thought. We could use that in Juneau.

I also saw remnants of the famous wall that divided East and West Berlin during the Cold War years that followed World War II. What initially prompted its construction (according to the guide on what I thought was an excellent Berlin history walking tour), was the sheer unpopularity of living in Stalin’s and later Krushchev’s eastern sector as compared to Eisenhower’s and later Kennedy’s western sector.

When Stalin died in 1953, my guide said, Soviet-appointed leaders in East Germany passed severe new work quotas that both increased hours and reduced pay for all the Germans living on the eastern side of the border, including the eastern side of the geo-political island of Berlin. German workers responded by staging a national strike. Soviets responded by sending in 15 Russian tanks that opened fire on the workers. The guide said about 200 East German strikers were killed that day, including about 50 in Berlin.

That became a threshold moment that lost the hearts and minds of most East Berliners for good, and they began to find their way across the barbed-wire border in greater numbers each day, voting with their feet. Soviet authorities countered by installing a series of inspiring public murals on their side of the border portraying how happy the working class had actually grown under Communist leadership.

When that didn’t seem to work, in 1961, they erected a wall three and a half meters high that even famed Russian high-jumper and world-record holder Valery Brumel couldn’t scale. It wasn’t to imprison East Berliners, the Communist authorities explained. It was an “anti-Fascist protection barrier.”

By any name, it failed to endear itself to East Germans, who continued to find clever ways to breach the wall, sometimes by means as daring as hot air balloons and zip lines. Still, it stood in place for 28 years. Until Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev — in the dawning days of the Information Age in the late 1980s — finally began to grant his people new freedoms. Which delayed but didn’t prevent the ultimate collapse of East Germany and the historic dissolution of the Soviet Empire a few years later.

Now all that’s old history too. Nearly a quarter century has passed since “the fall of the wall.” I was told that about half of the people living in Berlin today never even experienced the Soviet occupation, let alone that ugly period earlier when a mad man led their nation for 12 long years.

What they know is a vibrant, creative, new-millennium Germany with no Army and some of the most peace-loving citizens in Europe. Of course Germans vary as much as any other people, and regions within Germany vary too — from the prosperity of the politically conservative South I observed near Munich to the urban energy (and unfortunately longer unemployment lines) of the liberal North I saw in Berlin.

But I will go out on a limb here by saying Germans seemed to me to be more willing to publicly acknowledge the darkest days of their own history, including the Holocaust, than my own country is in terms of the lasting devastation of America’s original sin of slavery and racism. (Or as American author and Nobel Prize for Literature winner Toni Morrison once put it in an interview: “If Hitler had won the war and established his ‘Thousand-Year Reich’ … the first 200 years of that reich would have been exactly what that period was in this country for Black people.” I think you can quibble with her “exactly,” but not with her point.)

But I will go out on a limb here by saying Germans seemed to me to be more willing to publicly acknowledge the darkest days of their own history, including the Holocaust, than my own country is in terms of the lasting devastation of America’s original sin of slavery and racism. (Or as American author and Nobel Prize for Literature winner Toni Morrison once put it in an interview: “If Hitler had won the war and established his ‘Thousand-Year Reich’ … the first 200 years of that reich would have been exactly what that period was in this country for Black people.” I think you can quibble with her “exactly,” but not with her point.)

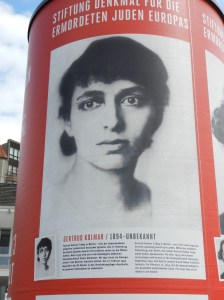

In Berlin, I saw Germany’s own dark chapter laid bare all over town:

In the haunting city-center Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, with it’s labyrinth-like rectangular columns that gradually grow taller and more menacing as you venture toward the center.

In the silent memorial opposing state censorship (simply, empty bookshelves) in the spot outside a university where Marx studied and Einstein taught — and Nazis very publicly burned 20,000 books they considered either subversive or impure.

In posters commemorating 2013 as the 80th anniversary of the Nazi regime’s accession to power — and the 75th anniversary of the anti-Jewish pogroms of Kristallnacht — in a Berlin government-sponsored initiative titled “Diversity Destroyed.”

And finally in the brochures advertising train tours to Sachsenhausen.

***

From the station in Oranienburg, we walked a couple miles down oddly unremarkable suburban streets to a field at the edge of town. There was a path there that led to the Sachsenhausen visitor center, which had a book store and a wash room and a door that led outside again. From there we walked along the camp’s outer wall to a courtyard with a guard tower and underneath it the Sachsenhausen sentry gate — still engraved with the once-universal Nazi message to new prisoners: “Arbeit macht frei” — “Work will make you free.”

The tour started slowly, incrementally. First we entered one of the last remaining barracks — there were once 68 like it, each housing up to 400 prisoners in a space suitable for one tenth that number. Prisoners slept there in three-decker bunk beds, sometimes two or three to a bed.

Each barracks contained seven or eight toilets, which created huge traffic jams in the morning when several hundred prisoners needed to use them at once. And if you missed that opportunity, you wouldn’t get a second chance until end of day, our guide told us. Above all, however, you didn’t want to miss the morning roll call, because the penalty for doing that was severe.

Roll call was held in front of the main entrance machine gun tower, which our guide said had “pan-optic vision,” thanks to the camp’s deliberate triangle shape. When a new prisoner arrived he or she was given a number, and that became their new identity. At roll call you needed to recite your number in perfect text-book German before you could be released, a feat that was especially difficult for foreign prisoners who didn’t speak Deutsch.

One infamous Sachsenhausen roll call was conducted in freezing weather in the winter of 1940 by Rudolph Hess, our guide told us. It droned on all day. Prisoners standing in place eventually began freezing to death. Some fell to the ground with the onset of hypothermia. Dozens more died during the night. By the following morning, according to Nazi records, 140 prisoners had perished.

During the 10 years it functioned as a Nazi concentration camp, Sachsenhausen served as a destination for a wide variety of prisoners — about 200,000 in all.

If you were ordered to wear an inverted red triangle on your shirt or coat, that meant you were a “political prisoner,” which might include virtually anyone who opposed the Nazi regime — from journalists to clerics to outspoken liberals and Communists.

If you wore an inverted black triangle you were a “social prisoner,” which meant you were either unemployed, or an alcoholic, or a homosexual, or a prostitute, or a Gypsy or anything Nazis considered anti-social. If you wore a blue triangle you were simply an emigrant, a non-German. If you wore a yellow triangle that meant you were a Jew.

(Our guide tried valiantly for about 15 minutes to explain the backstory of anti-Semitism in Europe, from early Christianity on, including the ghettoization of Jews that began around 1200 AD, the slurs about “Christ-killers,” the urban-legend of the blood libel, the manner in which Jews, even as late as the 20th century, became the default scapegoat for nearly anything that went wrong. Like the loss of territory Germany suffered in the Treaty of Versailles at the end of World War I. Then the hyper-inflation and staggering unemployment and long soup lines that followed with the Great Depression. Jews and Communists were to blame, Hitler said, and many of the least educated Germans believed him. After rising to power in 1933, Hitler managed to pass laws that prohibited Jews from working in several occupations, or attending certain schools, or using public parks and swimming pools. From then on they were a moving target for Hitler’s stormtroopers. Then came Kristallnacht, the bloody pogrom of 1938 that rounded up Jewish entrepreneurs, broke their windows and set their shops on fire…)

Right after Kristallnacht, about 6,000 new Jewish prisoners were admitted to Sachsenhausen, according to the camp’s official history. Jews there began to fill several of the barracks. By the fall of 1942, however, most of them were transferred to Auschwitz — as Jewish prisoners all over Germany were — by order of SS chief Himmler. There thousands were exterminated. Jews were murdered at Sachsenhausen too, as were thousands of Soviet prisoners of war. Executions usually occurred in a prison within the prison, a hidden place called Station Z where the Gestapo held sway. And that was the last stop on the tour.

There was a courtyard there with tall posts. Some of the prisoners scheduled for execution were simply handcuffed and hung by their wrists from the top of the posts, sometimes until they fainted from the pain, or arms tore from sockets. Then the Gestapo would drag the body to a manhole and drop it in, and place a slanted grate on top. And there the prisoner usually perished.

But in Station Z the Gestapo also maintained more efficient ways to kill prisoners, methods that weren’t as traumatizing to the elite cadre of officers who supposedly were going to father a master race once the war was over. One was an underground gas chamber complex, a prototype for others that would be introduced in the worst of the death camps in the last years of the war. According to Nazi records, its designers used Sachsenhausen to test different forms of gas to determine which was most effective.

Another was a firing squad room masquerading as a doctor’s office to set the prisoners at ease. Once they were brought inside, a pretend medic would check them for their vital signs, weigh them, then ask them to stand with their back against a wall under a measuring rod to check their height. Concealed behind the rod, however, was a firing device pointed at the back of the prisoner’s neck. With the push of a button behind the wall the prisoner tumbled forward dead.

According to camp records, in the fall of 1941, the Gestapo used the concealed shooting machine to execute over 13,000 Soviet prisoners of war — predominantly Jews and suspected Communist officials — in the single largest mass murder that would occur at Sachsenhausen. After they were shot, their bodies were taken to an adjacent crematorium and burned. Then their ashes were buried in an outdoor pit.

As the war finally wound down in April of 1945 — as Soviet and American troops marched ever closer to Berlin — Himmler ordered the camp evacuated. A census taken two months earlier determined there were close to 70,000 prisoners at both the main camp and its satellites. So thousands of the prisoners were summarily executed. Thousands more were transferred to other camps. But the largest group, about 33,000 prisoners, were ordered to join what came to be called the “death march” to the Baltic Sea. Though weak and starving, the long column of prisoners was forced by Gestapo guards to walk up to 25 miles a day. Thousands died along the way. More than half nearly made it to the ocean when, suddenly, their German guards disappeared, fleeing for their lives, as units of the Red Army and U.S. Army arrived to save them.

A long and complicated story to be sure, just as Nobel Laureate Elie Wiesel suggested at the onset. I left Berlin thinking about what he said. I considered a corollary. That either there was no religion or there was too much religion in a world that could allow an Auschwitz — or a Sachsenhausen. You wondered. You really wondered.

Dour Danes, revisited

Posted on August 25, 2013 Leave a Comment

As if Copenhagen isn’t pretty colorful already on a sunny summer afternoon (especially from the carefree vantage point of a bicycle), I had the good fortune Saturday of turning a corner on mine and suddenly finding myself in the center of a spectacular gay rights parade. Now was that fun or what?!

As if Copenhagen isn’t pretty colorful already on a sunny summer afternoon (especially from the carefree vantage point of a bicycle), I had the good fortune Saturday of turning a corner on mine and suddenly finding myself in the center of a spectacular gay rights parade. Now was that fun or what?!

In fact the half-day rental of the bike at a Danish Krone equivalent of $10 U.S. was the best bargain I found in the Danish capital. That and all the people-watching, which was free.

Saturday also marked the 100th birthday of the statue of the Little Mermaid in the Copenhagen harbor. So I biked over there later and paid my respects to Hans Christian Andersen — just before the rest of Copenhagen showed up for the beginning of a Happy Birthday, Little Mermaid fireworks show. Better make that the (not so) dour Danes.